immediacy

The Southern Literary Gentleman

One of the attractions of the biography is to study someone else's life and see just how difficult it was for them to achieve their success (for there are few biographies about failure), which on the outside seems so simple and pre-ordained, but once you review the life as it was lived, you see the stumbles and gaffes along the way. For someone once famous, whose star has since dimmed, this analysis can be truly bittersweet. James Branch Cabell was either the last or the first of a type of Southern Literary writer, depending on how you view his place in the pantheon. His genteel manners, adroitly expressed in his books, tie him to the old Southern tradition, where things were said in a certain way and men were expected to have ideals about life, expressed by Cabell in his philosophy of three approaches: the Gallant, the Chivalrous, and the Poetic. But Cabell was a sly one, too--the motto of his great work of fiction, the Biography of the Life of Manuel, was "Mundus Vult Decipit," which roughly translates as "the world wishes to be deceived," and Cabell was quite fond of deception. His mannered fantasies could be read in two ways--for the surface adventure and invention, or for the subtle (and sometimes not so subtle, as in the case of Jurgen) allusions and illusions in which Cabell commented on the mores of his Richmond, Virginia neighbors. Because, like his 1920s contemporary, Sinclair Lewis, Cabell was at heart a social commentator, struggling in his books to understand the changing world in a society that wanted to cling to outdated traditions and was being dragged, kicking and screaming, into a free new world of women's rights, the new free mobility due to the automobile, and a new streak of Puritanism that was Prohibition.

It's not unsurprising, then, that this biography of Cabell by Edgard MacDonald is titled James Branch Cabell and Richmond-in-Virginia, because Cabell was as much a product of Richmond as it was featured in his books (renamed as Lichfield). Born and raised in Richmond, the oldest of three sons of a druggist who married well, but was unable to please his wife, Cabell spent most of his first three decades as the constant companion of his mother, providing for her ego what his father could not. In addition to his mother, the other woman he fixated on was his first love while at college, Gabrielle Moncure. And because things always come in threes, the other woman in his life was his wife, Priscilla Bradley. The three of these women show up in his books constantly, under new names but always the same faces and personalities--the woman you admire, the woman you yearn for, and the woman you settle for.

Cabell's life was far from charmed, though. He struggled for money up until his thirties, when the marriage to Priscilla, a wealthy widow five years older than he, provided the economic stability he needed to focus on his writing. In turn, he provided an entree for her into Richmond society both by virtue of her marrying into the Branch family, as well as genealogical research into her own lineage that established her family tree as worthy of Richmond.

Of course it is Jurgen that is both the apex of Cabell's career and life, a storm of controversy for its lewdness and laviciousness that is quite tame in comparison to the steamy favorites of today such as Fifty Shades of Grey. But for the 1920s, and the new Puritans, Cabell's lance that wasn't quite a lance and staff that wasn't quite a staff was the kind of thing that titallated and shocked the matrons of polite society and the overseers of smut known as the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. No publicity is bad publicity, and although the injunction against Jurgen kept the book off the shelves for two years, it helped sell Cabell's previous novels and helped him make friends with his literary peers both in the U.S. and abroad. If he had moved ahead with new books, the story may have been different, but Cabell chose to instead re-work his previously published novels and stories, re-packaging of all of his work to date in a collected set, called the Storisende edition, that was basically a labor of vanity. Stating that all his works were connected, he re-wrote passages and provided introductions to make them so.

The downfall was not sudden, and was marked with some small joys along the way, but after the heady years of being the talk of the town (both Richmond and New York and Chicago), the reduced success of his remaining output made his latter decades more sour than sweet. He leveraged his friendship with Ellen Glasgow, also of Richmond, to encourage her to do a similar repackaging of her work, telling her that what she had written was a social history of Virginia, enough so that she began to believe it herself. He renamed himself to just Branch Cabell for most of his latter work, drawing a distinction between the author of The Biography of the Life of Manuel and his new creations, which likely didn't do him any good in the marketplace. And the loss of his wife, leaving him their only son to take care of by himself, upset his balanced life until he found another source of home stability in a marriage to a long-time friend, ten years his junior.

Edgar MacDonald covers all of this fairly well and in detail, but he's not a prose stylist, which is probably just as well, because Cabell had enough style for two writers. MacDonald observes a fair amount of restraint, covering some of the rumors and innuendo of Cabell's college years (including an event that hinted of an improper relationship between a professor and several of his students) without engaging in sensationalism. Unfortunately for any biographer, Cabell's second wife destroyed some of the more salacious documentation of his life before access was granted for a book, although Cabell would likely have approved of her actions, protecting his reputation from the curiousity of the maddening crowd.

Humor and Derision

The Cabell Scene by Robert H. Canary is an academic treatise from the late 70s on the major works of James Branch Cabell, a writer whom I have an inordinate fondness for and whom, in some form or another, will be infused into the book I am currently slaving away on. Canary's theme is that Cabell had two methods by which he attacked his subject--the pursuit of love: either through humor, as in his earlier work, or through derision, which most of his later work took form. The two are connected, and although Canary does a good job of making the distinction, the best part of this book is actually Canary's ability to illustrate some of the obscure issues in Cabell's work, and that is why I picked it up. Cabell was a master of obscurity with a purpose--he played games with the reader, using other languages, anagrams, metaphor, simile, etc. to sometimes hide his "true meaning." So much so that, in his most famous work, Jurgen, he was called a pornographic writer and the book and publisher were brought to trial by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. (In Jurgen, a sword could be more than a sword, and a lance could be more than a lance, but by today's standards, this is mighty tame stuff, as the reader must make the connections and use their imagination--the only author I can think of who used the same technique in modern time was Robert Anton Wilson in one of the Schrodinger's Cat books to replace all references to sexual genitalia and actions with Supreme Court justices: to this day, I can't think of Potter Stewart without a certain image coming to mind.)

I'm more familiar with the volumes that make up the Biography of the Life of Manuel, so Canary's discussion of the 1930s trilogy, The Nightmare Has Triplets, and the 1940s trilogy, Heirs and Assigns, was extremely useful to gaining more of an understanding and appreciation of Cabell's post-Biography work. In many ways, he became disillusioned following the heady success, and problems, that the notoriety of Jurgen brought him. The 1920s, in the 1930s, was considered the Cabell decade by many literature critics; by the 1940s, he had almost been totally forgotten. Never to let reality pass by without incorporating it into his work, the later novels are both bitter and bittersweet, as he struggled with that loss of fame and following. Thus, as Canary says, humor switches to derision, where Cabell had trouble laughing with life, but would rather laugh at it. Cabell reserved his jibes for the "typically Meckenian targets as patriotism, Philistinism, Puritanism, Prohibition, and preachers"--targets as ripe for jousting as today.

Is this something you need to read? No, not unless you are a scholar of the literature of the 1920s or a novelist intending to set his book in that time, with themes that touch on the "New South" and prohibition. If so, this can provide an interesting glance into one particularly urbane commentator of that society's mores.

An Impressive Achievement

Although I had read Craig Thompson's Blankets, and thought it quite fine, it did not prepare me for the amazing achievement that is Habibi. There is an incredible amount of care in each page, a thematic cohesion across the entire book, that this is finally a graphic novel that deserves the latter term. So many graphic novels come across as slight--often because they are simply collections of monthly serials that strive to create an overall story arc, but are often simply the stuff of melodrama. Thompson has truly created something that stands apart, and is worthwhile of your time.

Yet, I still only gave it 3.5 stars. Why? There's the rub. While I was impressed by Thompson's craft, and admired his themes, the underlying story itself failed to really connect with me. Having just completed living in Saudi Arabia for two-and-a-half years, I'm no stranger to the Arabic culture that provides the underlying cultural viewpoint, and I had done my own self study of the Arabic alphabet and could enjoy the intricate script work that Thompson achieved. But the biggest failing for this book for me is it's post-apocalyptic setting. I'm just not a big fan of what happens after the world fails to address climate change and things fall apart. While one can read and enjoy Habibi without focusing on its post-apocalyptic setting--you could try and read this as some kind of alternate world--there's just too much of it for me.

The story, without giving too much away, is about a young woman and an even younger boy who undergo change and transformation as they find each other, lose each other and themselves, and then refind themselves and the other. It's a very unusual love story, and it's about as much, if not more, about love in the abstract as it is about love in reality.

There are some harsh images here, both presented visually on the page and implied off the panel, as the plot contains some graphic description of sex--both good and bad--, childbirth, body mutilation, and poverty. But if you have a strong stomach, and want to read something like nothing else, this is recommended.

Writing the Novel: From Plot to Print

Lawrence Block describes the feeling one gets after finishing one's first novel here as akin to post-partum depression, and that description, along with so much more of this book, exactly encapsulates my own experience in writing the novel, and then being faced with a second one. Although published as a writing guide, Block's book is actually more of a psychological self-help tract to overcome one's own mental blocks in the writing process. If you don't have those blocks, you don't need this book. If you do (and I think that's probably more the majority of us), what Block does is help you realize that you are not alone, that these are mental traps that capture first-time novelists as well as seasoned professionals like himself. It doesn't make writing the novel any easier. As my friend Joe R. Lansdale told me over twenty years ago, the only way to write a novel is to "apply butt to chair and fingers to keyboard."

Lawrence Block describes the feeling one gets after finishing one's first novel here as akin to post-partum depression, and that description, along with so much more of this book, exactly encapsulates my own experience in writing the novel, and then being faced with a second one. Although published as a writing guide, Block's book is actually more of a psychological self-help tract to overcome one's own mental blocks in the writing process. If you don't have those blocks, you don't need this book. If you do (and I think that's probably more the majority of us), what Block does is help you realize that you are not alone, that these are mental traps that capture first-time novelists as well as seasoned professionals like himself. It doesn't make writing the novel any easier. As my friend Joe R. Lansdale told me over twenty years ago, the only way to write a novel is to "apply butt to chair and fingers to keyboard." I finished my first novel in 2001 and shopped it around, always thinking I would start a second one. In fact, I had several ideas floating around in my notebook and various computer files. But a combination of things prevented me from ever starting on it, including that mental depression facing the completion of that first one. As Block says, you start to think, "If that one's not good enough for publication, what makes me think my next will be?" But every book is different, the market changes, your writing is likely better for having written and experienced more in the meantime. Over ten years later, I'm revising that first book for possible eBook publication (i.e., market changes, where self-publishing has become a viable option, both logistically and monetarily) and I'm reviewing that set of notes and contemplating the second. I don't necessarily do the outlines that Block suggests that some writers do, but my own process requires that I have an idea of the theme of the book I'm writing. For me, writing needs to be a game I play with myself (an idea I first saw codified in Jane Smiley's 13 Ways of Looking at a Novel). In my first novel, the theme was evolution and the game was to incorporate as many references and imagery of development that I could, mainly centering around the concept of eggs.

While I don't shy away from reading fiction while writing my own, I do find reading books on writing stimulating for getting my own writing process going, as it focuses me on consciously thinking about choices covered by Block here like point of view and how the book actually begins. As Block suggests (although not in his own words): your mileage may vary. But this is a good overview of some of the driving options available to you.

The Quarry

This is basically Banks' version of The Big Chill: a group of college roommates meet up after many years to comment and reflect on their lives together and apart. Banks uses Kit, an OCD 18-year-old child of the oldest roommate, Guy, as the viewpoint character. Guy happens to be in the last stages of terminal cancer and into that mix, Banks throws in a macguffin of a videotape starring the roommates that each roommate would like to see destroyed, for their various reasons, but which Guy has lost or misplaced in the crumbling rooming house that he and his son occupy and which the others had lived in those many years ago.

This is basically Banks' version of The Big Chill: a group of college roommates meet up after many years to comment and reflect on their lives together and apart. Banks uses Kit, an OCD 18-year-old child of the oldest roommate, Guy, as the viewpoint character. Guy happens to be in the last stages of terminal cancer and into that mix, Banks throws in a macguffin of a videotape starring the roommates that each roommate would like to see destroyed, for their various reasons, but which Guy has lost or misplaced in the crumbling rooming house that he and his son occupy and which the others had lived in those many years ago.I call the videotape a macguffin because, while it ostensibly is the goal of all the characters, the point that the book actually revolves around is Guy's dying, and the point that the reader can't escape from is the knowledge that Banks, when writing this, was also dying of cancer. So, much more than in any of his other books, Guy becomes a stand-in for Banks himself, and when he rants against the unfairness of his lot, the divide between character and author gets mighty blurred.

Along the way, Banks revisits themes he had previous explored in [b:Complicity|12014|Complicity|Iain Banks|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1328396807s/12014.jpg|2132]: the playing of video games (in this case a Warcraft MMO clone based loosely on the Matrix movies), drug and alcohol use (and abuse), and the battle of individualism vs. corporatism. And, as the roommates were all film buff and/or majors, a lot of movie references pop up.

It's a bittersweet book, intentionally so. As a long-time reader and fan of Banks, reading it knowing that no more books will arrive from that source always lingers in the backbrain, but the ending is as good as an epitaph as can be had for someone who left us far too early.

Stand on Zanzibar

I first read this book as a teenager, and liked it so much that I listed it as a top ten favorite novel for decades afterward. In honor of actually having the opportunity to stand on Zanzibar myself during a recent vacation, I thought I would re-read it to see how well it held up. Thankfully, it does, although if I ranked all the books in my top ten, it would be a little further down the list these days.

I first read this book as a teenager, and liked it so much that I listed it as a top ten favorite novel for decades afterward. In honor of actually having the opportunity to stand on Zanzibar myself during a recent vacation, I thought I would re-read it to see how well it held up. Thankfully, it does, although if I ranked all the books in my top ten, it would be a little further down the list these days.When I read it long ago, I remembered it being much more disjointed. It is in parts, but I was able to connect the disparate pieces in my mind better, perhaps due to a familiarity with the prose and concept, even after these many years. I also hadn't remembered one of the lead characters being a Muslim, and likely glossed over that as a youngster, having never encountered a follower of Islam at that time.

[a:Bruce Sterling|34429|Bruce Sterling|https://d.gr-assets.com/authors/1379306689p2/34429.jpg]'s well-done introduction to the edition I read this time highlights some of Brunner's prescience, but what I found interesting was the near misses in Brunner extrapolation, specifically the entire concept that at some point in the future, people who have too many children will be ostracized by society for their lack of self-control and selfishness. Even at this point, after the world has doubled its population (from approximately 3.5bn when this novel was written to around 7bn today), I don't see any indication of this change in opinion--sadly, many cultures are the exact opposite, believing that they need to increase their population for fear that their culture will be overrun by others. Perhaps this is the real lesson of [b:Stand on Zanzibar|41069|Stand on Zanzibar|John Brunner|https://d.gr-assets.com/books/1360613921s/41069.jpg|2184253], that people (read large, as in the earth's population) will never be able to control their reproduction and the game of life will eventually collapse through disease, war, or famine.

Recommended? Yes, I would still highly recommend this book. It was a grand achievement when it was published, and it remains a solid work of art today.

Inside the Kingdom: Kings, Clerics, Modernists, Terrorists, and the Struggle for Saudi Arabia

My wife and I are about to begin an assignment in Saudi Arabia that will have us living there for months or possibly years, thus my need to quickly increase my knowledge about the Kingdom and its culture. This book by Robert Lacey is actually a follow-up to a much larger volume titled simply, The Kingdom, that Lacey first published in 1981. This, basicaly, is a sequel, but one written with the purpose of understanding the events that occurred after 1981 related to Saudi Arabia, specifically the war in Afghanistan, the rise of Al-Qaeda, 9/11, the embassy attacks within Saudi Arabia, and Guantanamo Bay. The title, therefore, is both accurate and inaccurate: if anything, Lacey's premise is that the last 30 years has forced Saudi Arabia to come to the realization that the Kingdom affects and can be affected by events outside its borders, for better or worse, and can no longer be denied by the King.

My wife and I are about to begin an assignment in Saudi Arabia that will have us living there for months or possibly years, thus my need to quickly increase my knowledge about the Kingdom and its culture. This book by Robert Lacey is actually a follow-up to a much larger volume titled simply, The Kingdom, that Lacey first published in 1981. This, basicaly, is a sequel, but one written with the purpose of understanding the events that occurred after 1981 related to Saudi Arabia, specifically the war in Afghanistan, the rise of Al-Qaeda, 9/11, the embassy attacks within Saudi Arabia, and Guantanamo Bay. The title, therefore, is both accurate and inaccurate: if anything, Lacey's premise is that the last 30 years has forced Saudi Arabia to come to the realization that the Kingdom affects and can be affected by events outside its borders, for better or worse, and can no longer be denied by the King.It's a fascinating book, and Lacey an engaging and smooth writer. Things I was able to learn from the narrative include finally understanding some of Saudi Arabia's attitude towards its neighbors (as well as sections of its own population) by Lacey's clear explanation of the Sunni and Shia differences. The book also illustrates the strange shift in Saudi attitudes towards hardline Muslim extremists and business-focused Westerners by focusing on several of the important power brokers in addition to the Al-Saud family.

The book was published in 2009, but based on what I've already learned from my first trip to the country, is in need of a couple of additional chapters, as Saudi Arabia continues to both embrace and fight a rapid pace of change. Just in the last year, a university dedicated to women's education has been completed near the Riyadh airport and several economic cities dedicated to trade, banking, and manufacturing are due to be completed in the next year. Women continue to press for more rights (not just the right to drive, but with regards to family and property rights) and the religious police have recently been pulled back from some more egrigious behavior. All of these are on a pendulum, one that Inside the Kingdom reveals can just as easily swing back in a more conservative direction.

It's going to be an interesting time here.

The Night Circus

It has been a long time since i have been extremely captivated by a novel so it is with joy that I reveal before I get to talking about the pedigree of this book, that it is a wondrous thing indeed and worth your purchase and perusal. Erin Morgenstern has crafted that rare avis, a debut novel that is so fully realized that it is hard not to think of it as the work of an established professional. If you want to go into this novel with no knowledge other than my heartiest recommendation, stop reading this now, I implore you, for what I may say below might take away some small bit of that wonder and surprise that I was allowed to enjoy, as I received this book as an advance reader's edition, with nothing other than a small publisher's blurb and an editor's invite to discover it for myself. I suspect that it won't be too many more weeks or months before this book and likely movie version is more well known.

It has been a long time since i have been extremely captivated by a novel so it is with joy that I reveal before I get to talking about the pedigree of this book, that it is a wondrous thing indeed and worth your purchase and perusal. Erin Morgenstern has crafted that rare avis, a debut novel that is so fully realized that it is hard not to think of it as the work of an established professional. If you want to go into this novel with no knowledge other than my heartiest recommendation, stop reading this now, I implore you, for what I may say below might take away some small bit of that wonder and surprise that I was allowed to enjoy, as I received this book as an advance reader's edition, with nothing other than a small publisher's blurb and an editor's invite to discover it for myself. I suspect that it won't be too many more weeks or months before this book and likely movie version is more well known.The Night Circus sits atop a mound of other books that have similar themes and plot devices, much like that comment by Newton that scientists have been able to reach great heights because they have been fortunate enough to stand on the shoulders of the scientific genius that went before them. While not as directly as Lev Grossman did in The Magicians, Morgenstern's novel reminds me of so many other good work, while at the same time never becoming less by doing so. For example, the concept of a magical duel over the ages recalls Christopher Priest's award-winning The Prestige, while the wonderful descriptions of illusion after illusion reminded me of Carter Beats the Devil by Glen David Gold, while the scenic background of the circus brought to mind both Angela Carter's byzantine Nights at the Circus as well as the more recent Like Water for Elephants (a story which I have only seen in film adaptation, albeit quite recently, which may be while it springs to mind). And while it isn't as densely intricate as the lush romance in A.S. Byatt's Possession, there is a love story herein with true feeling and power.

I hesitate to describe too much of the plot itself, which in this case would be akin to revealing how the magic trick is accomplished, but I do want the reader to be aware that this is a fantasy--but then, to steal a line from Alan Moore, aren't they all? Some people, however, are wary of magic, whether depicted as unreal or as a part of the fabric of everyday life, and while I pity them, I dislike to mislead. The central conflict between the two magicians, though, is conveyed in its own wrapping of written enchantment, that one could almost ignore the fantastical, if only to call it dreamlike. What I particularly liked about what Morgenstern has accomplished here is how she is able to capture the amazement of life as seen through the childlike wonder we attribute to the circus, and still keep to a plot-centric story that leaves you hanging on every chapter.

If you couldn't tell by now, I loved this book. It had everything I look for when reading: a fascinating setting, characters I could care about as well as understand (i.e., there is no stock villain present anywhere in this book), and a plot that was exciting as well as fulfilled by its ending. This novel deserves success and I look forward to what Erin Morgenstern can do to top this feat.

The Dud Avocado

I tried to read this book several times over the last two years, leaving it beside my bedside. Yet I could never get past the first twenty pages or so. In many ways, for a "classic," it is very much a contemporary novel: told in first person, more about character and place than plot, self-absorbed. Unfortunately, all three of those are things that make a novel less interesting for me personally.

I tried to read this book several times over the last two years, leaving it beside my bedside. Yet I could never get past the first twenty pages or so. In many ways, for a "classic," it is very much a contemporary novel: told in first person, more about character and place than plot, self-absorbed. Unfortunately, all three of those are things that make a novel less interesting for me personally.The basic premise is following a young, idealistic American girl in Paris in the mid-20th century. You may find this more your cup of tea if (a) you are a young, idealistic American girl or (b) you are interested in a picture of Europe in the middle of last century.

God Is Not One: The Eight Rival Religions That Run the World--and Why Their Differences Matter

A few weeks ago I read an interview with the author of this book and that intrigued me enough to make this the first purchase through Apple's iBooks application on my iPhone. During this last weekend's dive trip, and I had enough free time to spend educating (and re-educating) myself on the world's greatest religions. Prothero is a religious studies professor, and this book comes across as a basic college 101 survey course, albeit one that does have a thesis: that it is a mistake for people to claim that all religions are basically the same. Through chapters on Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Yoruba, Buddhism, Judaism, Confucianism, and Daoism, Prothero challenges you to question your perceptions of what you think religion is, what people want from it and what they believe that get from it, and how that works in a world where any two people who meet on the street will very likely have incredibly different viewpoints, even if they grew up in the same time and same place. (I hold this truth to be self-evident, given recent experiences reconnecting to family and high school friends on Facebook.)

A few weeks ago I read an interview with the author of this book and that intrigued me enough to make this the first purchase through Apple's iBooks application on my iPhone. During this last weekend's dive trip, and I had enough free time to spend educating (and re-educating) myself on the world's greatest religions. Prothero is a religious studies professor, and this book comes across as a basic college 101 survey course, albeit one that does have a thesis: that it is a mistake for people to claim that all religions are basically the same. Through chapters on Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Yoruba, Buddhism, Judaism, Confucianism, and Daoism, Prothero challenges you to question your perceptions of what you think religion is, what people want from it and what they believe that get from it, and how that works in a world where any two people who meet on the street will very likely have incredibly different viewpoints, even if they grew up in the same time and same place. (I hold this truth to be self-evident, given recent experiences reconnecting to family and high school friends on Facebook.)This is no self-help book. The goal here is not to provide a menu of religions so you can choose one to feast on for the rest of your life. Instead, it's the classic college assignment of compare/contrast, and in every case Prothero does a great job of doing so, and doing so in the context of each religion. That is, he uses the terms of the religion itself when doing the contrasting, rather than always comparing with his own upbringing.

Prothero does insert himself in the book, and it is better for it. It's important to know that he was raised in the Christian tradition, but also to know that he's attended Seders and has friends and colleagues in all these fields. His goal, beyond the thesis, is that by understanding the beliefs (or non-beliefs, as the case may be) of others, you are better suited to get along with them, and it certainly seems like he is a model example of this.

I come away from this book with as many questions as I went in, albeit ones that are different and more nuanced, more than likely. For one, I'm not sure that it is entirely possible that all these religions can co-exist peaceably, at least not under traditions that proselytize and seek converts, or where zealots seek to modify others' behavior based on their religious convictions. In this sense I do side with the New Atheists who feel that by allowing religion to enter the public, political realm is a clear and present danger. But Prothero is spot on to point to New Atheists being as starkly fundamentalist as the worst of any of the extreme wings of any of the religions, and that's enough to give anyone pause about their statements and goals.

This was the first book that I have read completely on my iPhone, and I very much enjoyed the experience. I didn't use the ability to make notes on the text outside of marking one typo, but I'm looking forward to taking advantage of that feature in the future. One time I did "lose my place" in the book, but finding where I was again was as easy as with the paper version.

Confucius Lives Next Door: What Living in the East Teaches Us About Living in the West

J picked this paperback up for me during her business trip in the U.S., due in part for her own interest in it, but also because we both had enjoyed Reid's informal talks with Bob Edwards on NPR's Morning Edition where he often provided a great first-hand view of an ex-patriate. Since we've been in that position for just a little over 18 months now, she thought I would find Reid's view of what the East gets right, and gets wrong, interesting. And I did. Reid is clear in his thesis, which may have aged somewhat since the book was written in the late 90s and thus doesn't cover some of the world changes that have occurred since. The background idea, that Asia is rapidly coming into its own and displacing the 20th century to make the 21st century the Asian century, is hard to refute. Reid's thesis, however, that this is due to a philosophy born out of Confucian thought, is a little tougher to follow, although he provides plenty of examples, both anecdotal and statistical.

J picked this paperback up for me during her business trip in the U.S., due in part for her own interest in it, but also because we both had enjoyed Reid's informal talks with Bob Edwards on NPR's Morning Edition where he often provided a great first-hand view of an ex-patriate. Since we've been in that position for just a little over 18 months now, she thought I would find Reid's view of what the East gets right, and gets wrong, interesting. And I did. Reid is clear in his thesis, which may have aged somewhat since the book was written in the late 90s and thus doesn't cover some of the world changes that have occurred since. The background idea, that Asia is rapidly coming into its own and displacing the 20th century to make the 21st century the Asian century, is hard to refute. Reid's thesis, however, that this is due to a philosophy born out of Confucian thought, is a little tougher to follow, although he provides plenty of examples, both anecdotal and statistical.The best thing about the book, however, is that Reid adopts a Japanese idea and points out the flaws in his own theory in an afterward (an atogaki). This is where I understood what was bugging me the most about the book, and that is trying to define Asia as a homogenous group. My personal perspective, having lived in Malaysia and visited (albeit too briefly for many of these places) other Asian locations, is that while some shared perspective is present, there's a lot more cracks in the impenetrable front that is often portrayed within and without the region. Malaysia, in particular, has a schizophrenia from its mixed racial identity and the growth of Islamic economic power. Reid, at one point, quotes a Chinese Malaysian as saying the affirmative action put in place to bring the Malay population out of poverty (in comparison to the Chinese population) was not perfect, but necessary for the culture, might still be said today, but that commentator would also say that it is time to change that affirmative action to one based on income, rather than race, as the ongoing New Economic Plan is increasingly seen as a racial divider rather than one that is actually improving race relations.

Finally, the other nice point that Reid emphasizes is that Confucian thought is actually not that far different from Christian teaching, with the golden rule of "Do unto others as you would have others do unto you" expressed as "Do not impose on others what you do not want for yourself." He then proceeds to make connections between other Judeo-Christian and Classical ethical guidance and Confucius, coming to the conclusion that, in a nutshell, ethics = ethics, in all languages and cultures. The difference may lie in how much individuals are willing to concede to groups, and vice versa (i.e., where are the commons, or where does your face end and my fist begin?).

Everyday Drinking: The Distilled Kingsley Amis

I joked with a family member who asked what I was going to read next that I hoped this was going to be a "how to" book. While it could conceivably be followed in some instances, Everyday Drinking is actually a collection of three smaller books that themselves were collections of the newspaper writings on alcohol by Kingsley Amis, more famous as the author of such novels as Lucky Jim and The Green Man, although it is pretty apparent from this book that he was more than familiar with the artistic merits of a couple of cocktails before and, especially, after the work day. This was a good addition to my growing library on bacchanalia, as it fulfills my rigorous requirements of (a) being more than just a recipe book (I have enough of those now, plus there's always the Internet Cocktail Database) and (b) having a strong, personal, opinionated voice. Amis has the latter in spades, as he ranges between saying that drinking is always a subjective enterprise to lambasting the heathens who would mix something with a single-malt scotch (even Drambuie, as in the Rusty Nail, which is better suited to mixing with a blend, in both his and my entirely not-so-humble opinions).

I joked with a family member who asked what I was going to read next that I hoped this was going to be a "how to" book. While it could conceivably be followed in some instances, Everyday Drinking is actually a collection of three smaller books that themselves were collections of the newspaper writings on alcohol by Kingsley Amis, more famous as the author of such novels as Lucky Jim and The Green Man, although it is pretty apparent from this book that he was more than familiar with the artistic merits of a couple of cocktails before and, especially, after the work day. This was a good addition to my growing library on bacchanalia, as it fulfills my rigorous requirements of (a) being more than just a recipe book (I have enough of those now, plus there's always the Internet Cocktail Database) and (b) having a strong, personal, opinionated voice. Amis has the latter in spades, as he ranges between saying that drinking is always a subjective enterprise to lambasting the heathens who would mix something with a single-malt scotch (even Drambuie, as in the Rusty Nail, which is better suited to mixing with a blend, in both his and my entirely not-so-humble opinions).Amis is clear that he's a beer man with a taste for gin, and that while he has some expert and experience with other liquor and wine, that's not where his heart lies. He does pretty well at covering the gamut, still, and as an intermediate wine drinker, I still found plenty to learn from him. These columns are somewhat dated, having been written mainly the in the late 70s and early 80s, as far as I can tell, but given that everything that once was old in cocktails is now new again, that's not so much of a problem. Finally, I was happy to obtain from this at least one new drink that I've quickly grown to enjoy quite a lot: the "Pink Gin," which is simply gin with a couple of dashes of Angostura (or other) bitters (I suggest serving it on the rocks if you don't keep the gin in the freezer as I do). It's a wonderful drink for those for whom adding ever the sight of the vermouth bottle to a martini reduces its dry nature; the bitters actually increases the dry quotient. Marvelous!

The Magicians

At some point in the development of a writer, you have to stop reading and start writing. Many writers find it difficult to write in their own style if they are simultaneously reading something very stylistic, as most writers are mimics--a thing that comes in quite handy when you are trying to write about characters very unlike you, but awkward in the case I'm describing where you unconsciously start copying another writer's style. This isn't confined to writers, of course, as musicians, painters, and most likely artists of any other stripe find that to create their own original work, they have to isolate themselves so that the influences aren't quite so immediate.

At some point in the development of a writer, you have to stop reading and start writing. Many writers find it difficult to write in their own style if they are simultaneously reading something very stylistic, as most writers are mimics--a thing that comes in quite handy when you are trying to write about characters very unlike you, but awkward in the case I'm describing where you unconsciously start copying another writer's style. This isn't confined to writers, of course, as musicians, painters, and most likely artists of any other stripe find that to create their own original work, they have to isolate themselves so that the influences aren't quite so immediate.Which makes it quite difficult for writers to work certain jobs, the worst being that of book critic or reviewer. Lev Grossman is the book critic for the news magazine, Time, and this is his second novel. I didn't read his first, Codex, but glancing at it recently in the bookstore, it was obviously marketed to the same folks who enjoyed the Dan Brown books (I can't say it's deriviative of Brown, as I didn't read the thing, as I said). This one, The Magicians, is very obviously a deriviative of the Harry Potter books crossed with C.S. Lewis's Narnia, and I might have dismissed it offhand if I hadn't seen some comments from people whose opinion I trust that said it was worthwhile. While they mentioned that it was "Harry Potter for adults," they noted that it transcended its source material.

Rather than transcend, I think The Magicians is actually a meta-fictional commentary on its influences, while retaining enough of an interesting story line that if you don't care about thinking in such ways, you don't have to. Grossman clearly takes on themes that Rowling avoided in her books, including much more believable turns on alienation and sexuality. There's also an implied criticism of C.S. Lewis's simplistic moralistic and structured adventures, and a devil of a villain that comes close to being original except that I think I've seen all of his special effects in horror/fantasy movies of the last decade.

I enjoyed the book quite a lot, but I would hesitate to suggest it to lovers of either of its major influences if they can't stand a bit of criticism, which seems appropriate in context, given Grossman's day job.

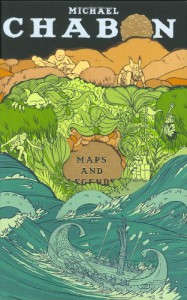

Maps and Legends

Pulitzer-prize winning Michael Chabon speaks to me and for me in this book of essays on writing. Chabon believes that fiction, specifically short fiction, has lost its power because of the limitations placed upon it by critics and other literary types, who turn up their noses at anything that smells like genre, unless it's written by an author who has an uncommon style. Direct prose that uses plot as much as character is anathema to these people, to which Chabon says, "get over it." Chabon, an unabashed fan of genre work (science fiction, fantasy, comics), provides a needed counterpoint to the New Yorker style where nothing ever happens in a story.

Pulitzer-prize winning Michael Chabon speaks to me and for me in this book of essays on writing. Chabon believes that fiction, specifically short fiction, has lost its power because of the limitations placed upon it by critics and other literary types, who turn up their noses at anything that smells like genre, unless it's written by an author who has an uncommon style. Direct prose that uses plot as much as character is anathema to these people, to which Chabon says, "get over it." Chabon, an unabashed fan of genre work (science fiction, fantasy, comics), provides a needed counterpoint to the New Yorker style where nothing ever happens in a story.Other essays in this slim volume cover some of Chabon's influences. I especially enjoyed his memoir of Will Eisner as well as the critical commentary on one of my favorite comics, Howard Chaykin's American Flagg! But even the essays on things I was more unfamiliar with, such as the use of the golem and Yiddish, were fascinating. Chabon's easy style and obvious enthusiasm for his subjects help make this volume fly by. In the end, you really do want more--although if it takes Chabon away from his fiction writing, perhaps we are better off with just this little bit.

Saucerful of Secrets: The Pink Floyd Odyssey

The recent demise of Pink Floyd keyboardist Rick Wright was my impetus for reading this well-researched biography of the rock group. I'm a fan of the Waters/Gilmour Floyd (as opposed to the Syd Barrett Floyd or the Waters-less Floyd), and Schaffner does a great job of distinguishing these different periods of the band, putting a nice perspective on the way the transitions occurred given the personalities involved. It's interesting to note that Floyd was unlike many other rock groups at the time, having grown up middle-class (or, in the case of Wright, upper-class), which partly explains their sound, which relied less on the three-chord blues imported from American (with which groups such as the Who and the Rolling Stones modified in their own ways to make popular both in Britain and back in the States) and more on experimentation, especially with sound effects. In fact, I hadn't realized just how important sound effects were to the Floyd sound until having this pointed out to me by Schaffner.

The recent demise of Pink Floyd keyboardist Rick Wright was my impetus for reading this well-researched biography of the rock group. I'm a fan of the Waters/Gilmour Floyd (as opposed to the Syd Barrett Floyd or the Waters-less Floyd), and Schaffner does a great job of distinguishing these different periods of the band, putting a nice perspective on the way the transitions occurred given the personalities involved. It's interesting to note that Floyd was unlike many other rock groups at the time, having grown up middle-class (or, in the case of Wright, upper-class), which partly explains their sound, which relied less on the three-chord blues imported from American (with which groups such as the Who and the Rolling Stones modified in their own ways to make popular both in Britain and back in the States) and more on experimentation, especially with sound effects. In fact, I hadn't realized just how important sound effects were to the Floyd sound until having this pointed out to me by Schaffner.I probably found the discussion regarding Syd Barrett the least interesting thing here, but that's due to my personal distaste of the psychedlic-style that was his hallmark. Others who like Barrett's music will likely find much to discover herein about Barrett, how both fame and constant LSD use took its toll on him, and how he was eventually ousted from the group that he ostensibly was the leader of. Of the other major change--the revival of the Floyd name sans Roger Waters--I was much more intrigued and found that Schaffner had done a good job in helping me see both sides of the issue. Personally, I think that Roger Waters and David Gilmour are like John Lennon/Paul McCartney: while both are good songwriters solo, they were great songwriters when they wrote together. Waters tends to be much, much too wordy in his solo material, neglecting the music and sometimes even the sound of the words, while Gilmour's lyrics are painfully juvenile at times (I never thought I would here "glove" rhymed with "love" in a Pink Floyd song).

For the true fan, this material may be old hat, but for the casual fan, this was an excellent overview of the Floyd career from the beginning to the classic rock concert circuit.

The Locusts Have No King

This was another book from Michael Dirda's list of 100 Best Humorous Books in the English Language, and another one that I enjoyed reading, but not so much for any comedy. I'd chalk it up to a difference of definition of what humor is, except so many of the books on Dirda's list that I had read I totally agreed with in regards to comedic intent and result. If anything, the list has got me trying books and authors that I had never heard of before.

This was another book from Michael Dirda's list of 100 Best Humorous Books in the English Language, and another one that I enjoyed reading, but not so much for any comedy. I'd chalk it up to a difference of definition of what humor is, except so many of the books on Dirda's list that I had read I totally agreed with in regards to comedic intent and result. If anything, the list has got me trying books and authors that I had never heard of before.What I did like about Dawn Powell's The Locusts Have No King was its portrait of literary life in New York City in the middle of last century, with its strange mixture of social and economic classes. The novel centers on the love affair of Frederick Olliver, an academically inclined writer of histories, and Lyle Gaynor, one-half of a married pair of playwrights with some recent success on Broadway. Lyle refuses to leave her husband, an invalid who depends on her partnership, and Frederick is too besmitten to insist on it. When a strange girl called Dodo attaches her social-climbing self on to Frederick just as he is heading to a society party that Lyle has insisted he attend, this delicate cocktail is upset, and the lives of Frederick, Lyle and everyone around them is changed.

This is a character-driven story, as the plot is easily summarized. Powell switches her point-of-view between the two main characters easily, and some of the frisson of this novel is how Lyle or Frederick so easily misunderstand the actions of the other (a staple of many comedies). I felt these situations, however, generated more pathos than bathos, as I felt sorry for these characters rather than bemused by their stubbornness. Maybe that's because I empathized too much with these two social-crossed lovers. Dodo, the "pooh" girl (called so for her tendency to call her beaus sticks-in-the-mud with the cry of "oh, pooh on you"), is almost as annoying as Fran Drescher's Nanny character, as you can almost hear that nasal voice in every piece of dialogue, and as Frederick becomes in turn besotted, obsessed, and disgusted with her, so does the reader.

Overall, an interesting novel, but not enough that I want to immediately check out more of Powell's writing.